Horsham Year of Culture 2019: “Horsham District Heritage in 100 Objects”

The Horsham District Heritage Forum received funding from Horsham District Council to carry out a project to identify 100 objects that best represent the heritage of the district, produce a book illustrating the selected objects (as well as a map giving information about where to see the objects that serves as a heritage trail) and organise a public exhibition as part of the Horsham Year of Culture 2019 celebrations.

The project is currently well on track for completion by the end of May next year. The synopses of the themes and sub-themes that will be used to draft the book have been agreed and the vast majority of the objects that will make up the total of 100 have been selected, whittled down from an initial number of just under 170.

The ten objects that were put forward by Cowfold are presented below.

1. St Peter’s Church medieval stained glass windows

Three medieval lancet windows in St Peter’s Church contain glass that is an example some of the oldest stained glass in the country and are therefore of great historical interest. They are also valuable as evidence of the style of glazing adopted by the medieval builders of the church, the first mention of which is in 1232.

Three medieval lancet windows in St Peter’s Church contain glass that is an example some of the oldest stained glass in the country and are therefore of great historical interest. They are also valuable as evidence of the style of glazing adopted by the medieval builders of the church, the first mention of which is in 1232.

Some of the valuable stained glass can be dated to around the middle of the 13th century, others to around the beginning of the 14th century. The windows themselves are characteristic of the simple early English architecture of the period.

The middle window contains a rare and beautiful example of a crucifixion set under an inscription and in a background of fragments of grisaille glass which are likely to date from the middle of the 13th century. The background depicts a conventional decoration of cowslips in this window and in the other two. ‘Grisaille’ is a term used for panels of clear glass with simple, often monochrome only, decoration.

The windows can be viewed in the church which is open to the public.

2. Capons Farm

Capons Farm (formerly known as Arnolds) is a medieval house and is the oldest in the Cowfold area. It is a good example of a Sussex Wealden yeoman’s house which has been subsequently extended and enlarged.

Capons Farm (formerly known as Arnolds) is a medieval house and is the oldest in the Cowfold area. It is a good example of a Sussex Wealden yeoman’s house which has been subsequently extended and enlarged.

In medieval times the farm, one of nine around Cowfold, belonged to the manor of Ewhurst in Shermanbury. The house is likely to have been first built as a yeoman’s house in the 13th century and the name Arnolds could have been derived from a Philip Arnald recorded as a taxpayer in the Subsidy Rolls record in 1296.

The house could originally have been an aisled two bay hall with outbuildings built between c 1300 and 1330. In the 16th century the growing affluence of the Wealden farmers allowed them to make substantial alterations to their original homes. Probably in the first half of that century Capons Farm was extended by the addition of a cross wing at right angles to the original hall; somewhat later an extension was built on the eastern side using brick for its façade. A chimney was also built on the side of the old hall.

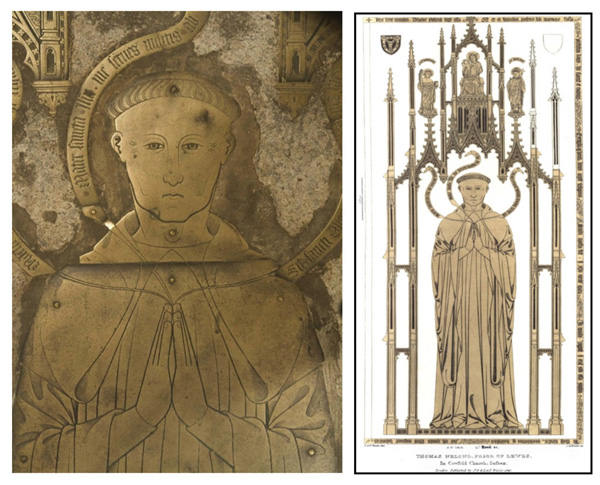

3. The Thomas Nelond Brass

The Priory was dissolved and destroyed in 1538 as part of the general dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. There is evidence to show that some families rescued threatened monuments to their kin from monasteries and installed them in the comparative safety of parish churches and this may have the case with the Nelond Brass. But why it was brought to Cowfold and installed in St Peter’s Church remains a mystery. Over 100 years had passed since his death and he would have left no direct descendants; nor was there any known connection with Cowfold. It cannot have been a straightforward task to move this massive slab a distance of 24km in the depth of winter.

The Priory was dissolved and destroyed in 1538 as part of the general dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. There is evidence to show that some families rescued threatened monuments to their kin from monasteries and installed them in the comparative safety of parish churches and this may have the case with the Nelond Brass. But why it was brought to Cowfold and installed in St Peter’s Church remains a mystery. Over 100 years had passed since his death and he would have left no direct descendants; nor was there any known connection with Cowfold. It cannot have been a straightforward task to move this massive slab a distance of 24km in the depth of winter.

The brass measures 3.1m (9’10”) x 1.3m (4’8”). The figure of the prior measures 1.8m (5’10”) and is thought to be life-size. He is represented tonsured and wearing the monastic habit of his order. He is flanked on one side by St. Thomas à Beckett, and on the other by St. Pancras, the patron saint of the Priory. Above his head sits enthroned the Virgin Mary, with the Christ Child standing on her lap. Short petitions to each saint rise in scrolls from his praying hands.

This is a rare survival of a brass to a monk. Once such compositions would have been commonplace, but most were destroyed following the dissolution of the monasteries.

The brass can be seen by arrangement with the Churchwarden.

4. Averys Barn

This timber-framed barn, most likely built around 1536, was mainly used for the storage of wheat, oats, rye or barley. It is probable that the barn was given a major overhaul in 1891, as this date has been scratched into two separate places on the building. The reason this late-medieval building has survived, when so many others didn’t, is probably because, at this time, barns were built by expert carpenters (due to the critical value of the goods stored in them). Other buildings were constructed by less skilled workmen such as the farmers themselves. So, when better technology and building skills were discovered, the less sturdy buildings were replaced with newer ones whilst the barns remained.

This timber-framed barn, most likely built around 1536, was mainly used for the storage of wheat, oats, rye or barley. It is probable that the barn was given a major overhaul in 1891, as this date has been scratched into two separate places on the building. The reason this late-medieval building has survived, when so many others didn’t, is probably because, at this time, barns were built by expert carpenters (due to the critical value of the goods stored in them). Other buildings were constructed by less skilled workmen such as the farmers themselves. So, when better technology and building skills were discovered, the less sturdy buildings were replaced with newer ones whilst the barns remained.

The barn was dismantled in 1980 and reconstructed in 1988 at the Weald & Downland Museum (who have kindly supplied the image).

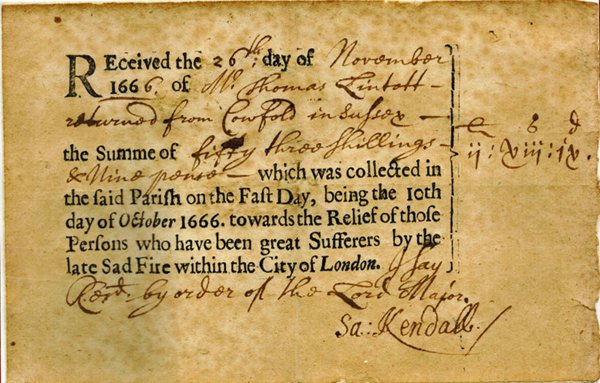

5. Cowfold’s contribution to helping London after the Great Fire

This receipt acknowledges the donation made by the village of Cowfold and the surrounding parish of 53 shillings and 9 pence (around £400 today), on 26th November 1666 towards the relief of Londoners who had suffered as a result of the Great Fire.

This receipt acknowledges the donation made by the village of Cowfold and the surrounding parish of 53 shillings and 9 pence (around £400 today), on 26th November 1666 towards the relief of Londoners who had suffered as a result of the Great Fire.

The Great Fire devastated London. There were few recorded deaths, but estimates put the destroyed property value at £10,000,000 (£1.5 billion in today’s money). After the fire much of London needed to be rebuilt. King Charles II ordered collections at churches across the country for the Lord Mayor of London to distribute amongst homeless and destitute Londoners. The total raised throughout the country was over £16,400 – covering 0.13% of the cost of repairing damage.

That the total sum raised was not greater is probably due to the country suffering ‘donation fatigue’ as only the year before it had been asked for money to help London recover from the Great Plague. People were also poor after the recent plague and civil war. In the 17th century Cowfold village and the surrounding parish probably had a population no greater than 100 persons so, in proportion, their donation was quite substantial.

This is one of a very few remaining examples of such a receipt and is on display at the Museum of London.

6. The Cowfold Church Marks

The Church Marks, also known as Pannells, surrounding St Peter’s Church could be the last surviving example of this form of enclosure in Sussex; no other examples have been found in any of the county’s villages. Cowfold’s Church Marks are therefore a unique historical record.

The Church Marks, also known as Pannells, surrounding St Peter’s Church could be the last surviving example of this form of enclosure in Sussex; no other examples have been found in any of the county’s villages. Cowfold’s Church Marks are therefore a unique historical record.

The Church Marks is a post and fence enclosure of the churchyard to prevent intrusion by animals. The fence is believed to have its origins in the Sussex Saxon tradition of this form of enclosure. The first mention of this fence is in the Parish Record for 1682; ‘A Particular of ye Church Pannells of Cowfold according to ye present owners being extracted out of ye old books October 9 1682’. This record identifies the names of houses and farms in the village and surrounding area, the people who lived there and the length of fencing that they were responsible for maintaining to enclose the churchyard. The Church Marks are therefore a valuable social as well as historical record of life in and around Cowfold and the surrounding area in the 17th century.

The fence and post enclosure is in a poor state of repair with only a few sections of the fencing now visible. The last time the Marks were renovated was in 1981. A project is underway to restore the posts and fencing using the original 17th century records and once completed this will be a focal part of the village’s history.

7. Margaret Cottages and the 18th century fire mark

Four houses stood on the northern boundary of Cowfold churchyard in 1635 one of which was “the parish house wherein Thomas Ellis now dwelleth”. The ‘parish house’ was the ‘poor house’ or ‘work house’. The house called Margaret Cottages, named after Margaret Norris who bought the house in 1926, converted it into six private alms houses and then rented them to the elderly of the parish, was originally the ‘Old Workhouse’ but is probably a successor to the building which stood there in 1635; it dates from around 1753.

Four houses stood on the northern boundary of Cowfold churchyard in 1635 one of which was “the parish house wherein Thomas Ellis now dwelleth”. The ‘parish house’ was the ‘poor house’ or ‘work house’. The house called Margaret Cottages, named after Margaret Norris who bought the house in 1926, converted it into six private alms houses and then rented them to the elderly of the parish, was originally the ‘Old Workhouse’ but is probably a successor to the building which stood there in 1635; it dates from around 1753.

The old Poor Law system provided relief on the premises of the workhouse or ‘poorhouse’ for those parishioners who were unable to maintain themselves. Under the Act of Settlement of 1662 this relief was confined to people who could show an established settlement in the parish. An early reference to Margaret Cottages is in the parish registers in 1773. In that year eight of its inmates died mainly from an epidemic of putrid fever. Poor Law expenditure was found from a parish rate levied on the rental values of properties and the fund was administered by two Overseers of the Poor appointed annually.

8. St Hugh’s Charterhouse, Parkminster

St Hugh’s Charterhouse is the only post-Reformation Carthusian monastery in the United Kingdom and so is unique to the country and Horsham District.

St Hugh’s Charterhouse is the only post-Reformation Carthusian monastery in the United Kingdom and so is unique to the country and Horsham District.

It was founded in 1873 to accommodate two houses of French Carthusians in exile so realising the first return of the Carthusian Order to England since the 16th century Reformation under Henry VIII which had resulted in the destruction of its twelve houses, the disbanding of the communities and the martyrdom of some monks.

The monastery was built on a large scale in order to accommodate two communities which were expelled from the continent. Building took place between 1876 and 1883. The number of monks has varied: 30 in 1883, 70 in 1928, 22 in 1984 and 26 in January 2017.

The buildings, in a French Gothic Revival style, were considered magnificent by Pevsner but who also thought that they “can only be properly seen from the air”. The church has relics of Saint Hugh of Lincoln, Saint Boniface and the Virgin Mary; and an unusually tall (203 ft) spire. It stands in the centre of other buildings including a library which contains about 35,000 books including manuscripts, a few of them dating from the 12th century, and a chapter house decorated with images of the martyrdom of the monks’ predecessors.

The Great Cloister, more than 115 metres long, is one of the largest in the world. It connects the 34 hermitages, which ensure the monks’ solitary life, to the church and the other buildings, embracing four acres of orchards and the monastic burial ground.

The Monastery only admits male visitors and usually by arrangement. However, the building can be seen from many vantage points in the area.

9. Cowfold Village Hall

The Village Hall is a fine example of the contribution made by a benefactor to the life of a village, in this case Frederick DuCane Godman, providing a focal venue for social activities that helped to bind the community together.

The Village Hall is a fine example of the contribution made by a benefactor to the life of a village, in this case Frederick DuCane Godman, providing a focal venue for social activities that helped to bind the community together.

The Hall was built in 1896 at a cost of £3000 paid for by Frederick Godman who lived at South Lodge, Lower Beeding and was a member of the family that contributed substantially to the village community.

The hall was officially opened on 17 December 1896 but before that had been used for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Tea. It very quickly became a focal part of the social life of the village, being used for a range of purposes including: an Annual Ball in aid of the poor until 1913, concerts and lectures, the Boys’ Brigade, dances during WW2, the Home Guard, a temporary schoolhouse for a school evacuated from Croydon in 1939, and a library and reading room.

The hall continues to be a significant focus for village life and is used actively by various community groups and for weddings and meetings of local organizations. The hall is very visible from the centre of the village but access is by arrangement with the caretaker.

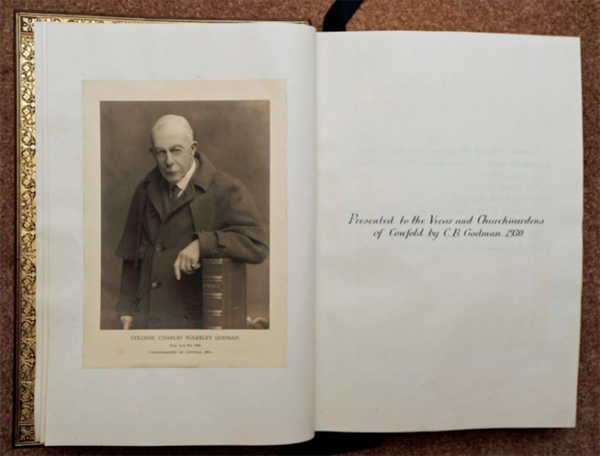

10. The Godman Book

The Godman Book is a unique and valuable illustrated record of Cowfold and the life of the community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with historical references back for many previous centuries in particular in describing St Peter’s Church and its treasures.

The Godman Book is a unique and valuable illustrated record of Cowfold and the life of the community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with historical references back for many previous centuries in particular in describing St Peter’s Church and its treasures.

The book was compiled by Colonel Charles Bulkeley Godman, one of a family who lived in and around Cowfold and were significant benefactors to the village community; he was the younger brother of Frederick DuCane Godman who funded the building of the Village Hall.

The book was presented to the vicar and churchwardens in 1930. It comprises 482 beautifully handwritten pages, produced using an ink pen, with black and white photographs and some beautiful watercolour paintings of the stained glass windows in the Church. It is bound in leather with handsome gold lettering and decoration.

As well as describing in detail the Church and its treasures, the book also describes the schooling available in the village, the various institutions and amenities that were available and some of the well-known characters who lived in or visited the village at the time.

The book is therefore an invaluable treasure trove and legacy of historical and social facts and records of Cowfold. The book belongs to the Church and is kept locked away. It can be viewed by arrangement with the Churchwarden.