Here is a historical account of plagues and pandemics as they have affected the country and Horsham District that was produced by the Horsham Museum team.

The Justinianic Plague

Names can tell us a lot about the origins of a place. Horsham – a place where horses breed, Storrington – a place where storks can be found, Slinfold – a pen for sheep, Cowfold – a place for penning cattle before taking them into the woodland meadows, and Henfield; not a field of hens, but a high field. These are just a few examples of villages in Horsham District that get their name from their geographical location, the local flora and fauna, or occasionally from the name of an owner. Interesting, all of these names have a post-Roman origin, their Roman names have disappeared. The explanation for this is extremely topical for, towards the end of the Roman Empire, the Justinianic plague ravaged Europe from 541-750AD.

The Justinianic plague killed around 13-26% of Europe’s population. Much like the later Black Death, the plague was transmitted by the fleas found on rodents. When the Saxons arrived in Sussex, they didn’t come to a land teaming with people but to a wilderness of woodland and scrub. They therefore chose local features to name the towns and villages.

The Black Death

Companion Carpenter – Fragment of a Woodcut from the Fifteenth Century, after a Drawing by Wohlgemüth for the Chronique de Nuremburg

After 600 years of population growth, in 1348 the Black Death arrived on our shores and spread rapidly throughout the country. Caused by the same bacteria that caused the Justinianic plague, the Black Death pandemic killed an estimated one third to two-thirds of the population of Europe. The Black Death was a debilitating illness that caused fever, fatigue, swellings in the groin and armpit, festering sores, and often lead to death. If you were lucky enough to survive you were likely to be scarred for life. The Black Death affected everyone, even those who didn’t catch the disease, as it impacted the entire country socially, psychologically and economically. Unfortunately, we do not have any contemporary accounts of its specific effect on Horsham; however, we can use information about similar towns and villages to estimate the impact of the Black Death on our town.

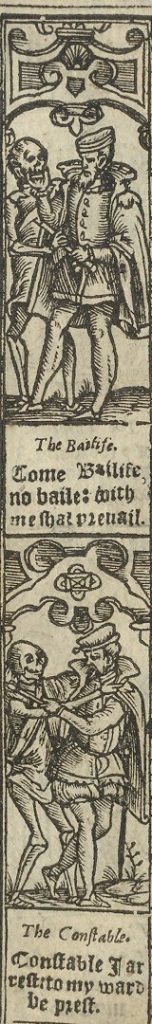

Images of death stalking the land from a 1570s Book of Common Prayer

In the Middle Ages people believed that the Black Death was transmitted via dirty air, or “miasma” and some people chose to flee urban areas for more rural ones in the hope that cleaner air would protect them. Despite the devastating impact of the Black Death, and the enormous death toll, life had to continue. We can also assume, based upon actions taken elsewhere, that markets and fairs stopped trading initially, making towns seem far more quiet than usual. As the death toll mounted up there was increased lawlessness in medieval society. Judicial and administrative work continued, and the demand for military equipment didn’t dip. Farmers continued to sell their goods produce food, although with fewer people to feed it was essential to ensure that any price rises were kept in check.

Construction also continued, with surplus housing (often abandoned due to widespread fatalities) dismantled and the material redistributed. In 1357 one Horsham house was bought for 66s 9d and taken apart, with the stone from the roof taken to Steyning, and the timber being sold in Horsham for 16s 8d.

The Black Death kept reappearing sporadically until around 1400. The 1361 outbreak was known as the “mortality of children” as it particularly affected the young. In 1369 and 1375 it killed a further 10 per cent of the population. The large number of deaths meant that there was a shortage of workers in key trades. This was particularly true for the Wealden Iron industry, which had relied heavily on seasonal workers, or those in other trades (such as farming) looking for supplementary incomes. Due to the mortality rate of the Black Death, many farm labourers were able to take up tenancy in vacant farms. Demand for iron remained high as life began to return to normal, arms were needed for war and equipment was required for farming and construction. To combat the labour shortage, and encourage people to work in the iron industry, wages rose to 150% of their pre-Black Death level. As the following account recorded for the Manor of Petworth in 1349/50 shows, increased wages meant rising prices:

“…and for iron bought for maintaining the ironwork of the ploughs this year 8s 4d, and so much because iron is dear by reason of the mortality”.

We don’t know how many people died of the Black Death in Horsham District; however, as the state started to keep better records of the population in order to collect taxes the impact of later plagues are better known. The plague struck Horsham in 1560 with a death toll of 111, the following year 68 individuals died, then it lay dormant only to strike again in 1574 when 62 died, dropping to 27 deaths in 1575 and 30 in 1576. For twenty three years there were no further outbreaks in Horsham, until 1599 when 91 died. These figures may seem low compared to the horrors of the Black Death but, as a proportion of the population it was significant.

The Great Plague of London

In 1665, the Great Plague of London struck, leading to the deaths of around 100,000 people, almost a quarter of the city’s population. In the first week of September 6,988 deaths were recorded London. This resulted in a financial crisis as the rich, and many of the clergy, left the city as soon as they could, without concern for the poor. Nonconformist ministers, who had previously been excluded from returning to their previous parishes under the 5 Mile Act, returned to tend the sick. The nonconformists would preach, tend to the sick and condemn the depravity and vanity of the court. Quakers also remained in London to tend the sick and 1,177 of their number died during the Great Plague. They used their connections to rural areas to channel relief into the city and held meetings requesting relief for the victims of the plague. Whilst we know today that the plague was probably spread by fleas on rats, in London money was set aside for killing 40,000 dogs and 80,000 cats, the very animals that would have killed the rats. The King asked rural areas to help as trade was at a standstill in London. Horsham, due to its close proximity to the capital, was also affected by this loss of trade. With the first frosts the plague abated and by February 1666 Court was resumed and within a generation the population of London had recovered.

Spanish Flu

The next big pandemic to hit Horsham was Spanish flu, just over 100 years ago. Spanish Flu had largely been ignored in history books as the death toll was considered part of the bleak overall picture of the First World War, yet it killed many millions of people worldwide. However awareness of the devastating impact of the Spanish flu has increased as people have become more aware of the impacts of such epidemics, perhaps due to the recent incidences of SARS, Avian flu and Swine flu. The scale of the Spanish Flu was such that an estimated 3-6% of the world’s population died, and the mortality rate is estimated at anywhere between 10 and 20%.

Horsham was deeply affected by the outbreak. The log book of Horsham High School records the following:

“July 11 to 15 Miss Findlay absent with influenza. Many pupils absent through influenza + bad weather.”[1]

Spanish Flu, so named because Spain (which was neutral at the time) had a free press and covered the outbreak in greatest detail, was first noted in Glasgow in May 1918 and had reached London by June. Unlike most flu viruses, Spanish flu attacked young adults more violently than the old and the very young, and when it did attack people could die in a day. In a letter dated 29 September 1918, Professor Roy Grist, a Glasgow physician, described the deadly impact of the infection:

“It starts with what appears to be an ordinary attack of la grippe. When brought to the hospital, [patients] very rapidly develop the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission, they have mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis [blueness due to lack of oxygen] extending from their ears and spreading all over the face. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible.”

The horror of the Spanish Flu didn’t stop the children in the playgrounds of Britain singing this ditty:

I had a little bird

Its name was Enza

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.

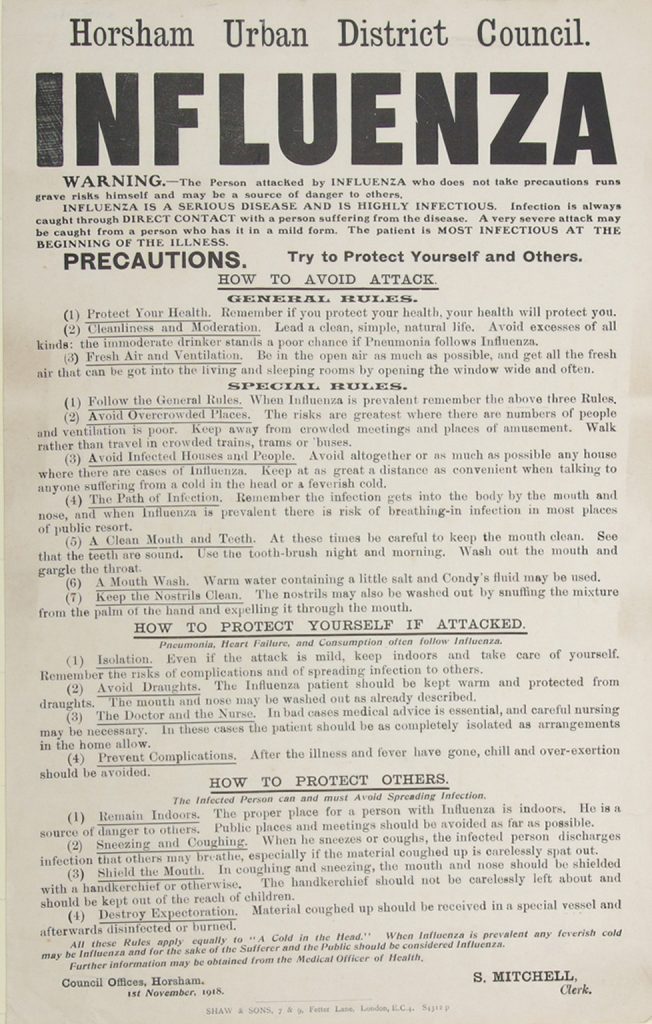

In late October/early November 1918 the local Council’s Medical Officer advised that they publish precautionary posters and instructions for use in the District. By 6 November the Clerk could report that he had distributed the poster around the town. This message came too late for many people, including some staff and pupils at Horsham High School where the log book records:

“Oct. 22nd Closed school for a longer half term as 25% of girls absent from influenza, + Miss Wagstaff still absent (tending her sick father) Miss Walker Student teacher also absent. Oct.29 Reopened School. Miss Wagstaff still absent (her father died on Oct. 27) 30 pupils absent through influenza.” [2]

Although the Council could do little in the way of providing direct assistance it at least understood the scope of the problem and provided its residents with the information to help. Across the country Councils were spraying streets with disinfectant, closing meeting halls and shutting theatres. Unfortunately the Council minutes do not record any such actions by Horsham Urban District Council. The Waterworks and Lighting Committee minutes of 19 October do, however, record the effect of the flu on its staff. The plumber Mr. Child, who was running the waterworks machinery in the absence of the engineman Freeland, was taken ill with influenza. Temporary assistance was obtained from Messer’s Holloway to do the pumping until the 21 October when Freeland was able to resume work. Three days later, on the 24 the plumbers mate, Mr Whittington, also fell ill with influenza, so that Freeland was then the only one of the waterworks staff capable of duty. The scope of the flu was so great that by December the Government issued a circular concerning regulations placed on public entertainments.[3]

However, one such gathering that people did not want to miss out on was the Armistice celebrations. The High School for Girls pupils were taken to Church at 12 and as reported much of the town celebrated. Nationally this led to a second wave of infection. On 3 November 1918, a week before Armistice was called, the News of the World reported a number of ways to combat the epidemic, some of which are not very appealing:

“Wash inside nose with soap and water each night and morning; force yourself to sneeze night and morning, then breathe deeply. Do not wear a muffler; take sharp walks regularly and walk home from work; eat plenty of porridge.”

Despite its considerable impact, within two years the Spanish Flu had been consigned to history books.

Spanish Flue Poster from 1918

References