The Little Gate through which the Carthusians re-entered Sussex

The Little Gate through which the Carthusians re-entered Sussex

By Mrs Bancroft-Hughes

Published in a Christmas issue of “Catholic Fireside” magazine in the first half of the 20th Century

Foreword

The Society’s archives include the following document, which is a transcript of an article published in the Catholic Fireside, a monthly, then weekly, magazine produced between 1878 and 1978. The article includes a charming account of how the Carthusians acquired land, then called the Picknoll Estate, in Cowfold in order to build the monastery that is now such a prominent landmark within the village. The article has been digitised and uploaded to our website so that it can be shared with residents and others interested in the history of Cowfold.

The “Little Gate” Article

Since there can be very few persons, if any, still living besides myself, to whom are known the circumstances I am about to relate with regard to the return of the ancient and venerable Order of the Carthusians into England, the following brief account may be of interest to our readers.

My grandfather who, as I first remember him, was an aged man of somewhat terrible aspect, wearing a small round black wig, had made a considerable fortune in early life, and, some time before my birth, had settled in a country house at Cowfold in Sussex on the road to Bolney, making his surroundings delightful by gardens, orchards and fishponds.

About this time, he purchased another and smaller estate in the same parish, called Picknowle, or Picknoll, as it is described in the older maps. This was a place possessed of great natural advantages, and, in the same year that I was born, he further embellished it by planting an avenue of lime trees on one side of the road leading from the turnpike to the farmhouse – the same lime trees that now shade the fine carriage drive by which is approached the entrance to the Sussex Chartreuse of St Hugh at Parkminster.

On the death of my grandfather this property was inherited by the eldest of his eight sons, who was my father and under his skilful designs the old and inconvenient farmhouse was enlarged, modernised and improved into a possible summer dwelling for us, its name being changed to that of “Parknowle” by my father, who, without delay, began to consider the choice of a favourable site for building a large family mansion from his own plans.

An ardent lover of all things beautiful, and a very gifted landscape gardener, my father found at Parknowle great natural advantages towards the exercise of his inclinations, and before long the foundations of his cherished scheme were being laid on the brow of a gentle eminence overlooking the woods and pasture lands of the vast Weald, stretching away to the purple Downs in the south, and commanding a matchless view from the eastern to the western horizon.

Gradually arose the stately and well-proportioned edifice, with solid square tower in the centre and wide terrace well raised on the south and east, which now (shorn, alas! of tower and terrace, and with the rich dark red tiles of the gabled roof replaced by a plain slated roof in the French style) does duty as the guesthouse of the good monks.

A most delightful old country lane, deeply sunk between matted hedges of oak and hazel, led from the farm to the public road, and idyllic ponds crowded with tall bulrushes, and tangled thickets of honeysuckle and dogrose, made the place a very paradise for children, whilst the banks of the great sandpit from which the sand was daily carted for the new house were literally tunnelled by the sand martins, those clever little burrowers who baffle the curious pursuer.

My father was very happy in turning a large meadow into a well-stocked orchard, bordering it with a high hedge of sweet briar that was a sight of beauty for the whole parish, the scent being distinguishable for a great distance, and it was soon bristling with standard roses of every shade and description. His strawberries carried off prizes in every show, the pears and apples from the new trees were simply monsters, the squirrels crowded in from the neighbouring woods to feast on raspberries and filberts, and the red brick walls by the stable were soon covered with prolific peach trees, such as are rarely met with in those parts of Sussex.

In the midst of this wealth of beauty, this natural luxuriance of fruit and flowers, of animal and bird life which thronged Parknowle, there was always a strange sensation about the place that I have never experienced anywhere else. It was a sort of suspense, a waiting, as it were, for some spiritual presence – a kind of supernatural expectancy. And this at times and in certain parts of the woods and grounds overwhelmed me so irresistibly and with so much force that now, nearly fifty years after, I can quite easily recall the peculiar thrill that possessed me in this strange way. It was as if Nature waited for angels’ visits.

Meanwhile the building went on apace. I have observed, in reading the late gifted Monsignor Benson’s story “The Conventionists”, that he makes one of his characters speak of the morning room at Parknowle (Parkminster now) as “beastly”, and I think he would have been very differently impressed by it, could he have seen the long narrow windows opening onto the raised terrace – which, of course, was demolished long before his time – and realised that the gilt cornices and painted dadoes were in completest harmony with the rest.

My father must have been a very strong man as well as very tall – he was considerably over six feet – for I remember, at the time when scaffolding, ladders and rope-ways prevailed, he expressed a wish to show me a view of the sea which could be seen from the top of the great tower, and, tucking me under his arm, for I was a small child then, he actually carried me by that break-neck road up to the extreme height, giving me a full view of the wide noble Weald such as is seldom seen except from the top of the highest of the Downs, and then carrying me back again as easily as if I had been a kitten – nor had I any fear in his company, but it was a daring escapade.

However, lovely as Parknowle was already and lovelier as it promised to become under the skilful hands, it was not without drawbacks. The heavy cold clay of the land made my mother always ill there, and the expenses drained my father’s income too heavily. More than once I heard him say he feared he could never live there, and once I remember he said it with tears, for he was very wrapped up in the place.

We always wintered in Brighton, where our home-house was, and, about this time, I, who was a sociable little child, made friends with a dog – a dear, long-haired dog that was brought often to our paddock for a ramble; probably to eat grass! It was some time before I became aware that, whilst I was making friends with the dog, he had an appendage – a mistress, in fact – who was trying to make friends with me; and not long after, I received an invitation to tea – to tea with the dog, of course.

My mother objected strongly. “Those people”, she said, “are Roman Catholics, and harm may come of it.”

But I wanted to go to tea with the dog, and go I did, not once only, but several times; paying much attention to him, and very little to the members of the family, who, so to say, “belonged to the dog”.

At one of these tea parties, I, long-tongued as usual, was chattering about my country home, how nice it was, and how papa couldn’t afford it and had said he would have to sell it.

Suddenly an old gentleman who used to be there at tea, but who had never spoken to me before, said: “What do you say, little girl? Your papa wants to sell Parknowle?”

“Yes,” I said, “he does. He says it costs too much, and makes mama ill, besides.”

“Are you quite sure of it?” he asked again; and I thought him a very queerly-behaved old gentleman to ask me the same thing twice, and that he was not half so nice as the dog. But the little gate was opened.

Now my father had been brought up a staunch, old-fashioned Protestant. I am afraid that, at this time, “Jews, Turks and Roman Catholics” were very much of a muchness to him. He was very regular and devout in his religious duties, extremely charitable to the poor and sick, tender-hearted and compassionate, a most loving father and genial host. But Roman Catholics were outside of our horizon, and therefore it was very novel and surprising to us all when Father (afterwards Monsignor) J. N. Denys, the worthy Catholic priest of West Grinstead, began to call on my parents. Hewas not only a Roman Catholic, but a priest, and we children were not, at first, allowed to come in when he was calling.

But his genuine bonhomie soon worked on my warm-hearted father, and they became great friends. After a time the good priest came accompanied by one or two foreign gentlemen, and sometimes they would go over the house and grounds with my father without anyone seeming surprised.

One day, however, my youngest brother, who was about sixteen then, I think, and had been out with them on one of these excursions, electrified us all by observing, in the bosom of the family, “Do you know, I believe those friends of Father Denys’ are monks.”

“Monks?” we cried out, laughing at the bare thought of such an impossibility. “Whatever makes you say such a thing of poor Father Denys?”

The boy cogitated, as if unable to formulate an impression – and then it came out.

“Because their clothes look so odd on them – as if they aren’t used to them – that’s all”; and we derided him, and he was “boo’d” out of court as a crude critic!

My father had not the least suspicion that the Russian friend of Father Denys’, by name Baron Nicolai, was anything more or less than a foreign nobleman who wished to purchase an English estate as his private residence. If he had known that the purchase was being made for a monastery of any kind, I think he would, from a conscientious scruple, have been unwilling to consent to it at this time, though afterwards, when he came to know the Carthusian Fathers, his views became very much modified, and it was certainly less painful to him in some ways, than it would have been had another entered into his beloved inheritance as its personal possessor. The actual state of the case never dawned upon him until, the purchase being concluded, and the deeds actually signed, Baron Nicolai, formerly aide-de-camp to the Emperor of Russia, who was wrapped in a large fur cloak, for it was winter, and who had, of course, not mentioned the fact that he was now Dom Jean-Louis, wrote as his address by the side of his signature, “Grande Chartreuse.”

“Do you live near the Grande Chartreuse?” asked my father

“No”, was the reply: “I live in the Chartreuse itself.”

“But that is a monastery. Is there a village as well?”

”There is a village; but I live in the monastery.”

“Are you a monk, then?” “Yes.”

“What! I thought I was selling my house to a Russian nobleman – and I have sold it to a monk?”

“You have not been deceived,” said one of the Carthusians who was present at the signing of the deeds, “he is the Baron Nicolai, sometime aide-de camp to the Russian Emperor.” “In that case,” said my father, “let us be friends.”

And in future he remained a friend, not only to the Carthusians of Parkminster, but to the Catholic Mission of West Grinstead also.

This account was given to us by my father on his return home, not without some amusement, for, as he said, “they had me in a corner!” It is to be found almost word for word as he told it to us in a French book by Max de Trenqualeon called “West Grinstead et les Carylls” [Burns & Oates, London, & M. Torre, 51 Rue S. Anne, Paris].

A very small proof of this good feeling may be mentioned. Finding that the strict abstinence of the Carthusians permitted the use of moorhens (called dabchicks in Sussex) – on account of their partaking of the cold-blooded nature of fish, I believe – my father often sent a little bag of these birds from the ponds of his outlying farms for the use of the Fathers. Certainly, contact with the Carthusians produced a good effect on him. His prejudices seemed to soften in a great measure, and he was struck by the “spirit of the Order”, which he thought a very admirable thing. He told us how, one day, when walking with a Carthusian at Parknowle, the monk stopped occasionally, and taking from his pouch a walnut or chestnut, planted it very carefully. My father, watching him, and thinking perhaps of the many trees he had himself planted, said rather sadly “You will never see these trees grow up! Walnuts grow very slowly!” To which the monk replied quietly but with emphasis: “I shall not, but we shall.”

The same words spoken by another monk on a different occasion made the impression even deeper. I think it was the acting Superior who was observing that more land was needed around the monastery, in order to ensure solitude and isolation, for the Parknowle estate was but a pocket-handkerchief laid down in the wide Weald – and the monk pointed out some property near, which the Order, he said, would be glad to acquire.

“No chance of that,” replied my father: “it belongs to ….” (naming a large landed proprietor of violently anti-Catholic opinions), “and you’ll never get it.”.

“To which the monk made the same reply: “I may not, but we shall,” and then he added, smiling pleasantly; “We can afford to wait.”

The “largeness” of this made a very good impression; and again, the brightness and humorous simplicity of the austere men quite delighted my father. This, of course, appeared in trifling things, one of which amused him immensely.

The English-speaking of the Carthusians, who were all Russians or Frenchmen, was limited. In the course of settling the details of purchase, the question of fixtures came up now and again.

“Fixe⸍? Fixe⸍?” said a monk; and several kinds of fixtures (landlords’ and tenants’, and so on) having been carefully explained, the thing evidently struck him as drolly puzzling, and, pointing to the wide carriage-drive which lay white and glistening from a recent light fall of snow, he asked with a sly look of good humour: “And he – is he ‘fixe⸍’, too?”

All these trifles, small as they were, had excellent effect in giving a larger and sunnier view of Catholics and of religious[sic], and when, some years later, my father’s favourite daughter was received into the Church, he showed no bitterness or resentment, but, on the contrary, treated her always with the greatest affection and kindness, though he was deeply hurt at a saying that came to his ears, to the effect that her conversion was a “judgment on him for having been the means of the Carthusians finding a home in Sussex.”

The generosity of the monks was not lacking in his regard. On the conclusion of the purchase, a huge packing case arrived, together with a most courteous note from the Father-General of the Carthusians, asking my father’s acceptance of some liqueur, in remembrance of the transaction they were pleased to have had together. The great flasks of yellow and green Chartreuse, so well-known to all men, were accompanied by small bottles in wooden cases of an elixir, which my father gravely concluded was given to the brethren when they fainted from long fasting.

This polite gift came as a great surprise, and the graceful kindness with which it was tendered made it doubly acceptable.

A little while afterwards, my father put a thick paper package in my hand, saying, “That represents Parknowle – it may perhaps be a long time before you hold sixteen thousand pounds in one hand again!”

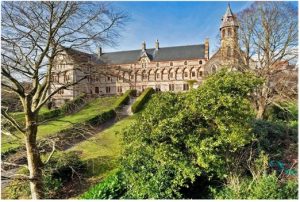

Now, I will write nothing of the wonderful Chartreuse, with the longest cloisters in the world, as existing at Parkminster today, nor of the holy lives of prayer and solitude led there by the Carthusians in their extensive monastery, nor of the rich blessing which they bring to Sussex and to all England. This has been told over and over again far better than I could tell of it. My object is only to tell of the little gate, and the way it was opened and entered, as not being generally known.

May I, therefore, only add in conclusion, that it needs but to see the fair tall spire of the Minster dominating the whole county, and to hear the sweet Angelus bell, or the constant deep voiced tolling of the great midnight call of the monks to the Divine Office, in order to be penetrated with gratitude to God for the supernatural Faith thus constantly witnessed to in the midst of an unbelieving generation, and to feel that the visits of the Angels have indeed extended to Parknowle!

Footnote

Which period did the article cover?

We know from online records that:

- Before 1831, Charles Lee sold Great Picknoll to John Macpherson, who, around 1840, owned 110 acres in Cowfold

- By 1854, he had sold the estate to William Boxall

- William Boxall died in 1863 and the estate passed to his son, William Percival Boxall

- In 1866, W. P. Boxall built a Jacobean mansion in flint

- In 1873, William P. Boxall, sold Great Picknoll (or Picknowle) to the Carthusian order

- Building of the monastery commenced in either 1875 or 1876

- Work was completed and the monastery was consecrated in 1883

- The mansion built by W. P. Boxall became the guest house of the monastery (although it lost its central tower and some of its crenelations and was rendered in cement.)

Therefore, the “opening of the little gate” episode probably took place in the latter part of the period between 1866 and 1873 and the father in the article was almost certainly William Percival Boxall.

What do we know about the Boxall Family?

William Percival Boxall ((1814-1898) married Caroline Money in 1845 and together they had nine children – seven daughters and two sons (although one daughter, Ela, died before the age of one). They were:

Caroline (1846-1907), William Percival Gratwicke (1848-1931), Jane (1850-1901), Charles (1852-1914), Ela (1853-1853), Alleyne (1856-1927), Christiana (1858-1950), Gertrude (1863-1930), and Anne (1864-?). Their mother Caroline died shortly after Anne was born, presumably from exhaustion.

William Percival was a man of considerable substance and, on his death in Brighton in 1898, his probate records him as having two houses, Ivories, Cowfold, and in Brighton. He left £49,530 (around £4 million in today’s money!), which his eldest son, William Percival Gratwicke, would have inherited; at the time of his father’s death, William P. G. was 50 and two years away from becoming a King’s Counsel.

There is one mention of William Percival being an architect that could account for the description in the article of “under his skilful designs, the old and inconvenient farmhouse was enlarged, modernised and improved…”.

There is also mention halfway through the account of “my youngest brother” that probably refers to Alleyne.

So, who was the author of the article?

The simple answer is that we do not know for certain.

During the period that we believe is covered by the account (between 1866 and 1873), Caroline would have been between 20 and 27 years old, Jane between 16 and 23, Christina between 8 and 15, Gertrude between 3 and 10 and Anne between 2 and 9.

So, the reference to “tucking me under his arm, for I was a small child then…” points to either Christiana (if it took place early in the period), Gertrude or Anne.

Further investigations revealed that Christiana became a Benedictine nun at St Scholastica Abbey, Dawlish Road, East Teignmouth, Newton Abbot, Devon. (The abbey has subsequently closed and been converted to private apartments.) Records show that Christiana died in Devon in 1950.

Further investigations revealed that Christiana became a Benedictine nun at St Scholastica Abbey, Dawlish Road, East Teignmouth, Newton Abbot, Devon. (The abbey has subsequently closed and been converted to private apartments.) Records show that Christiana died in Devon in 1950.

Turning to the article text, we have one passage:

“All these trifles, small as they were, had excellent effect in giving a larger and sunnier view of Catholics and of religious[sic], and when, some years later, my father’s favourite daughter was received into the Church, he showed no bitterness or resentment, but, on the contrary, treated her always with the greatest affection and kindness, though he was deeply hurt at a saying that came to his ears, to the effect that her conversion was a “judgment on him for having been the means of the Carthusians finding a home in Sussex.”

We can be confident, therefore, that “my father’s favourite daughter” was Christiana.

Gertrude appears in marriage records in Brighton in 1888; she married a solicitor, George Clifford Henfrey, in 1888 and they had 13 children. She died in 1930 in Brighton, still with her married name of Gertrude Evelyn Henfrey.

There is very little information on the youngest daughter, Anne, and we don’t know when or where she died.

As there is no record of anyone from the family marrying a Mr Bancroft Hughes, it is difficult to surmise where that name came from, unless it is a nom-de-plume – but why?

It is clear from the final concluding paragraph that, whichever daughter wrote the article, she was a deeply religious person:

“May I, therefore, only add in conclusion, that it needs but to see the fair tall spire of the Minster dominating the whole county, and to hear the sweet Angelus bell, or the constant deep voiced tolling of the great midnight call of the monks to the Divine Office, in order to be penetrated with gratitude to God for the supernatural Faith thus constantly witnessed to in the midst of an unbelieving generation, and to feel that the visits of the Angels have indeed extended to Parknowle!”

The author also writes about her feelings of Parknowle and its “spiritual presence”:

“In the midst of this wealth of beauty, this natural luxuriance of fruit and flowers, of animal and bird life which thronged Parknowle, there was always a strange sensation about the place that I have never experienced anywhere else. It was a sort of suspense, a waiting, as it were, for some spiritual presence – a kind of supernatural expectancy. And this at times and in certain parts of the woods and grounds overwhelmed me so irresistibly and with so much force that now, nearly fifty years after, I can quite easily recall the peculiar thrill that possessed me in this strange way. It was as if Nature waited for angels’ visits.”

Catholic Fireside – The Catholic Magazine for the Home

Several Catholic publications started up in the 19th century, including “The Catholic Times” that, we understand, gradually became the most widely circulated Catholic paper in England. A special London edition was produced and, in 1878, a Christmas supplement issued under the title of “The Catholic Fireside” was so successful that it was continued as a monthly penny magazine with the first edition published on 31 January 1879. In 1893 it was made a weekly magazine and publication ceased with the 4,514th edition on 29 September 1978.

The “Little Gate” article was included in a Christmas edition of the magazine but we have been unable to determine the year. The only hint that we have is that the author refers to recalling sensations “nearly fifty years after”. This would suggest that it was written in the first two decades of the 20th century but this, of course, is just supposition.